The legal profession has always been a novelists’ treasure house, and lawyers themselves are a gift to writers of fiction. If your plot has wound itself into a hopeless tangle, you can often solve matters by allowing the family solicitor to discover old documents or a Will which will provide motives the reader hasn’t yet suspected exist, (and that the author didn’t realise were going to be needed). There can even be the discovery that the solicitor has forged the Will/siphoned off the trust fund/faked a promissory note – even pilfered the petty cash – thus giving him/her a credible motive for one or two juicy (or even judicial) murders, and so becoming the villain of the piece.

The legal profession has always been a novelists’ treasure house, and lawyers themselves are a gift to writers of fiction. If your plot has wound itself into a hopeless tangle, you can often solve matters by allowing the family solicitor to discover old documents or a Will which will provide motives the reader hasn’t yet suspected exist, (and that the author didn’t realise were going to be needed). There can even be the discovery that the solicitor has forged the Will/siphoned off the trust fund/faked a promissory note – even pilfered the petty cash – thus giving him/her a credible motive for one or two juicy (or even judicial) murders, and so becoming the villain of the piece.

Wills can be very useful to an author. If a house needs to be empty for a number of years, one way to achieve this is by a Will’s disappearance. For Property of a Lady, I created an old-fashioned firm of lawyers whose senior partner wore a high-wing collar, and whose office was crammed with decades of stacked-up deed boxes. The gentleman died at his desk – he was found by a junior clerk, but several sets of vital documents were not. This allowed the property – Charect House – to stand empty for a very long time, crumbling into suitably gothic dereliction while the ownership was disputed and fruitless searches made for the Title Deeds.

Wills can be very useful to an author. If a house needs to be empty for a number of years, one way to achieve this is by a Will’s disappearance. For Property of a Lady, I created an old-fashioned firm of lawyers whose senior partner wore a high-wing collar, and whose office was crammed with decades of stacked-up deed boxes. The gentleman died at his desk – he was found by a junior clerk, but several sets of vital documents were not. This allowed the property – Charect House – to stand empty for a very long time, crumbling into suitably gothic dereliction while the ownership was disputed and fruitless searches made for the Title Deeds.

Comedic lawyers in fiction are regarded with affection. John Mortimer (himself a former barrister), knew this when he created Rumpole of the Bailey, memorably portrayed on TV by Leo McKern. Frequently awash with his favourite claret (‘Chateau Thames Embankment’), Horace Rumpole cheerfully wrought havoc in his Chambers, doled out wise, if not always practical, advice to juniors, and generally managed to confound most judges before whom he appeared.

Other writers, however, were not always favourably disposed to the legal profession. Shakespeare, in Henry V1 Part 2, gives one character the line, ‘First thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers’. Hamlet, exchanging macabre pleasantries with Horatio in the graveyard and considering a disinterred skull, asks, ‘Why may not that be the skull of a lawyer?’ And in Goethe’s Dr Faust, the hapless doctor grumpily observes that, ‘All rights and laws are transmitted like an eternal sickness.’ Given that poor Heinrich signed a legal document that went horribly wrong, perhaps the sentiment is understandable.

Charles Dickens drew on his time as a solicitor’s clerk (a job he apparently disliked), and as a court reporter, to weave satirical portrayals of the English legal system, with characters caught like hapless flies in the dusty spider strands of the law. When, in Oliver Twist, Mr Bumble advised a court that, ‘The law is an ass’, Dickens may have been borrowing from a 17th century play called Revenge for Honour, which is attributed to both George Chapman and Henry Glapthorne, depending on which source you check. Not much seems known about Henry Glapthorne, but apparently Master Chapman signed an agreement for a loan which never materialised. According to the reports, he spent years petitioning Chancery to release him from payment, but at one stage was arrested for debt. (A fate which hovers over many writers to this day). Under those circumstances (supposing the facts to be accurate), it’s hardly surprising that Master Chapman did what a great many other writers have done: he wrote out his frustrations in the plot.

Charles Dickens drew on his time as a solicitor’s clerk (a job he apparently disliked), and as a court reporter, to weave satirical portrayals of the English legal system, with characters caught like hapless flies in the dusty spider strands of the law. When, in Oliver Twist, Mr Bumble advised a court that, ‘The law is an ass’, Dickens may have been borrowing from a 17th century play called Revenge for Honour, which is attributed to both George Chapman and Henry Glapthorne, depending on which source you check. Not much seems known about Henry Glapthorne, but apparently Master Chapman signed an agreement for a loan which never materialised. According to the reports, he spent years petitioning Chancery to release him from payment, but at one stage was arrested for debt. (A fate which hovers over many writers to this day). Under those circumstances (supposing the facts to be accurate), it’s hardly surprising that Master Chapman did what a great many other writers have done: he wrote out his frustrations in the plot.

Recently I came across the term “infangentheof”. I had never encountered it, but it seems that the literal translation is “in-taken-thief”, and it permitted the owners of a piece of land the right to mete out justice to miscreants captured within their estates, regardless of where the poor wretches actually lived. It’s an Anglo-Saxon arrangement, supposedly from the time of Edward the Confessor, but when the Normans came barrelling in, they made cheerful use of it as well, because it helped keep the rebellious Saxons in their place.

Infangentheof fell more or less into disuse in the fourteenth century. But one afternoon, having become lost in the depths of the countryside, I came across a field with a sign on the gate saying, ‘Infanger’s Field’. A fragment from the past? A shred of some long-ago feudal baron who had named a field as a warning to miscreants? I made eager notes, although it was a bit unfortunate that I dropped my notebook in the mud, (I think it was mud – I hope it was mud), and perhaps I wouldn’t have worn scarlet gloves if I had known there was a bull in the field. I’m doubtful if I could find the field again. It might not even exist. It might have been time-slip land – a fragment of the medieval era that had momentarily slipped through a tear. Being prosaic, it’s also possible that a Mr or Mrs Infanger might live – and farm – in the area. Whatever the truth, the notes are perfectly legible (even if the paper is somewhat pungently scented), and I daresay the bull enjoyed eating the woolly gloves I threw to him by way of diversion while I scrambled over the gate to safety. Writers go to considerable lengths to get a plot sometimes.

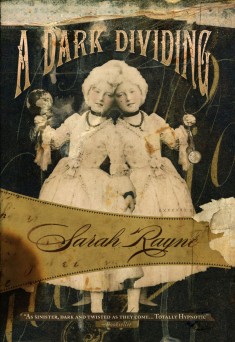

Writing A Dark Dividing some years ago, I searched for an appropriate house name for the brooding old orphanage/workhouse that played such an integral part in the plot. Names of places matter just as much as names of characters. You can’t call a Victorian asylum Rosemount Manor or a gaol housing condemned prisoners Summerville Court. Then I came across the word mortmain, which opened up another unknown chink of law. The Statute of Mortmain (ie dead man’s hand), dates back to around 1200. The kings of that time used to hand out land to religious houses, but after a while it dawned on them that the owners of the land would never actually die – ownership simply passed from abbot to abbot. That meant the medieval equivalent of death duties were never payable. So the Mortmain Law was created to close up this loophole and allow the monarchs to scoop up the dosh. A cynic might wonder if the law was also intended to check the growing wealth of the church, but whatever the reasons behind its creation, it gave me Mortmain House.

Writing A Dark Dividing some years ago, I searched for an appropriate house name for the brooding old orphanage/workhouse that played such an integral part in the plot. Names of places matter just as much as names of characters. You can’t call a Victorian asylum Rosemount Manor or a gaol housing condemned prisoners Summerville Court. Then I came across the word mortmain, which opened up another unknown chink of law. The Statute of Mortmain (ie dead man’s hand), dates back to around 1200. The kings of that time used to hand out land to religious houses, but after a while it dawned on them that the owners of the land would never actually die – ownership simply passed from abbot to abbot. That meant the medieval equivalent of death duties were never payable. So the Mortmain Law was created to close up this loophole and allow the monarchs to scoop up the dosh. A cynic might wonder if the law was also intended to check the growing wealth of the church, but whatever the reasons behind its creation, it gave me Mortmain House.

The law, with all its quirks and archaic convolutions, provides remarkably good plot devices for authors. There are tithes and torts and peppercorn rents. There’s assumpsit (medieval breach of contract), and gavelkind (a Saxon form of limited land ownership).

Since Magna Carta a great many of those old laws have been repealed. Some remain though, and traces of others can still be found today. Even if one of those traces is simply a field that might once have known the ancient practice of infangentheof, but that now houses only an indignant bull.

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Property-Michael-Flint-Haunted-House/dp/1847513476/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1456305848&sr=1-6

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Dark-Dividing-Sarah-Rayne-x/dp/1934609803/ref=tmm_pap_title_3?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1456305848&sr=1-5