I wasn’t expecting to find I had combined an ancient law and opera for a book, but Song of the Damned, (Book 3 of the Phineas Fox series), turned out to have both elements at its heart.

I wasn’t expecting to find I had combined an ancient law and opera for a book, but Song of the Damned, (Book 3 of the Phineas Fox series), turned out to have both elements at its heart.

It’s not, of course, so very rare for opera and the law to meet up. In Lohengrin Wagner invokes the laws of the Holy Grail as part of the plot, while, at the other end of the spectrum, Gilbert & Sullivan light-heartedly satirize the legal system for Trial by Jury, spattering it with cheerful quarrels over breaches of promise.

But it was a far older law and a much more modern opera that inspired the plot of Song of the Damned.

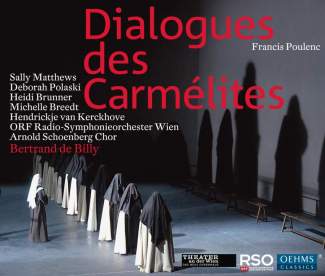

In 1953, Frances Poulenc composed an opera called Dialogues of the Carmelites.  It relates the grim and emotionally-charged, true story of the imprisonment of sixteen Carmelite nuns during the French Revolution. They were captured because of their religious beliefs, and subsequently executed. The execution seems to have been an extraordinary piece of theatre – of which Poulenc makes full use. The nuns were forced to form a queue for the guillotine, and to mount the scaffold one by one, with the most junior novice being first. As they waited for death, they re-affirmed their religious vows aloud, and sang various hymns, (reports vary as to what the hymns actually were depending on which source you use). The singing was punctuated by the relentless fall of the guillotine for each nun, their voices gradually diminishing as each was beheaded, until, at the last, only the lone voice of the Mother Superior was to be heard. And then there was silence.

It relates the grim and emotionally-charged, true story of the imprisonment of sixteen Carmelite nuns during the French Revolution. They were captured because of their religious beliefs, and subsequently executed. The execution seems to have been an extraordinary piece of theatre – of which Poulenc makes full use. The nuns were forced to form a queue for the guillotine, and to mount the scaffold one by one, with the most junior novice being first. As they waited for death, they re-affirmed their religious vows aloud, and sang various hymns, (reports vary as to what the hymns actually were depending on which source you use). The singing was punctuated by the relentless fall of the guillotine for each nun, their voices gradually diminishing as each was beheaded, until, at the last, only the lone voice of the Mother Superior was to be heard. And then there was silence.

This was a scene that had great impact on me. The dreadful inevitability of the massive guillotine blade swishing down – the helpless progression of the nuns towards it. But then – as is frequently the way with novelists – I began to wonder whether there might be a plot to be found in the story. Poulenc had already made use of it, of course, and so had one or two other people. A writer called Georges Bernanos wrote a screenplay around it, and the text of that was based on an earlier short story – The Last at the Scaffold written in the early 1930s by Gertrud von le Fort.

So it looked as if the fount had been squeezed dry. Or had it? Supposing a plot could be woven from the left-overs? Supposing those original nuns could be given links with other nuns – maybe a small convent community in a rural corner of England… And supposing Phineas Fox, the music historian whose third outing this was to be, found a lost medieval ritual within a locally-written piece of music – a macabre ritual and a piece of music that could be traced back to those nuns…?

So far so good. What about the setting, though? As anyone who has read any of my books will know, I’m keen on atmospheric settings and I’m very keen indeed on houses and buildings with intriguing histories.

It was at that point in the deliberations, and in the early and difficult stages of drafting a plot, that I came across a fragment of a very old English law.

It happened by purest chance. One afternoon having become lost in the depths of the countryside, I drove past a field with a sign on the gate saying, ‘Infanger’s Field’.

Infanger’s Field?

The English countryside is, it must be said, liberally strewn with strange and intriguing names. Quite near to where I live is a village called Coven. It’s an extremely nice place, but its name is always very deliberately pronounced ‘Coe-Ven’. Purists carefully point out that the name derives from the Anglo-Saxon, cofum¸meaning either a cove or a hut, but despite that, there are occasionally dark mutterings suggesting that the place once had witchcraft associations, and that the pronunciation was politely slurred to hide that fact.

Then there are all those instances of Glue Works Lane and Slaughter Yard. There’s Pudding Lane where the Great Fire of London reputedly started in a baker’s shop. On the other hand, there are places whose names are open to interpretation, such as Cockshutt in Shropshire, which, despite sounding like a venue for a Carry On film, is likely to derive from fowl hunting activities. Other names are satisfyingly rooted in the past: Oxford has Brasenose College and Brasenose Lane – supposedly from the Brazen Nose door knocker of the original sixteenth century Hall. Incredibly, though, the city also once had the now-lost Shitbarn Lane, c.1290, which ran between Oriel Street and Alfred Street.

But Infanger’s Field?

I dashed home to scour bookshelves and the internet. The bookshelves yielded several indignant spiders, dispossessed of their homes, and a couple of dictionaries and encyclopaedia with ageing pages but legible information. The internet provided several alternative spellings for the word and about 3,000 search results.

And it seems that the word comes from the Old English infangene-þēof – ‘Thief seized within’ or ‘in-taken-thief’. Infangenthief or infangentheof, no matter how you spell it, was, an Anglo-Saxon arrangement, supposedly from the time of Edward the Confessor – c.1003-1066, and one of the last of the royal House of Wessex.

And it seems that the word comes from the Old English infangene-þēof – ‘Thief seized within’ or ‘in-taken-thief’. Infangenthief or infangentheof, no matter how you spell it, was, an Anglo-Saxon arrangement, supposedly from the time of Edward the Confessor – c.1003-1066, and one of the last of the royal House of Wessex.

It apparently permitted the owners of a piece of land the right to mete out justice to miscreants captured within their estates, regardless of where the poor wretches actually lived. On occasions it also allowed the culprits to be chased in other jurisdictions, and brought back for trial. The justice that was meted out was often extremely severe – there was no cheerful Gilbert & Sullivan principle of letting the punishment fit the crime in those days.

The privilege of exercising this law was granted to feudal lords, and inevitably to religious houses. And later, when the Normans came barrelling in they made cheerful  use of it as well. It helped keep the rebellious Saxons in their place. The law fell more or less into disuse in the fourteenth century and all-but vanished from England’s history. Except for the occasional name here and there. Like Infanger’s Field.

use of it as well. It helped keep the rebellious Saxons in their place. The law fell more or less into disuse in the fourteenth century and all-but vanished from England’s history. Except for the occasional name here and there. Like Infanger’s Field.

I have no idea if it was a fragment from the past I encountered that day – perhaps a shred of some long-ago feudal baron who had named a field as a warning to miscreants. And I’m doubtful if I could find the field again.

But there it was. A long-ago storyline involving a group of nuns in the French Revolution and a macabre musical ritual. And there, too, was the potential for an atmospheric house that could be given the name Infanger’s Cottage. A house whose present-day occupants might find themselves forced to make use of the ancient law to guard the secrets that dwelled in the cottage’s foundations – secrets that stretched back to those long-ago nuns and the ritual that had been part of their mysterious story.

SONG OF THE DAMNED is published 31 July in the UK and 1 November in the US.

Source: Sarah Rayne Blog